Fort Pitt Steel Casting

© 2007 Jason Togyer, all rights reserved.

Background | Cooperation Breeds Innovation | Conglomeration’s Toll |

Falling Behind | Last Chance

|

|

Fort Pitt Steel Casting’s simple mark on the side of valves, pipe fittings, and other parts represented a mark of excellence for much of the 20th century. |

|

In the first half of the 20th century, McKeesport’s Fort Pitt Steel Casting Co. represented the state-of-the-art in the foundry business. The plant developed new techniques that enabled it to reliably cast molten metal into parts and tools needed by factories, railroads and shipbuilders for the rapid industrialization of the United States.

By World War II, the technology and experience represented at Fort Pitt allowed the company to produce high-quality products for defense work won the plant and its employees a coveted U.S. Navy maritime “M” award for excellence.

Swept up in the conglomerate boom of the 1950s and ’60s, Fort Pitt began faltering. The national media focused on Fort Pitt in 1979 when workers staged a last-ditch effort to save the plant through an employee stock-ownership plan that was a model for other companies.

But time was against the McKeesport foundry. Wall Street machinations, lack of investment, friction between labor and management, and foreign competition had combined to send the company into a death spiral from which it couldn't recover.

Background

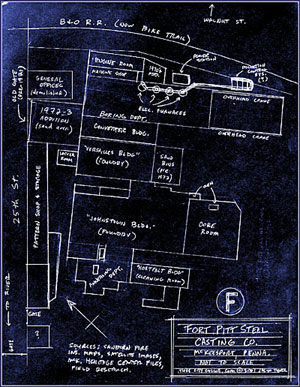

Founded in 1906 by C.S. Koch, Fort Pitt Steel Castings Co. was built on 13 acres in what was then Versailles Township, but eventually became part of McKeesport’s 11th Ward. The new firm capitalized on McKeesport's fast-growing steel and iron industries and its location convenient to railroad and river transportation as well as supplies of scrap metal, coal, and coke — materials essential to the foundry business.

|

|

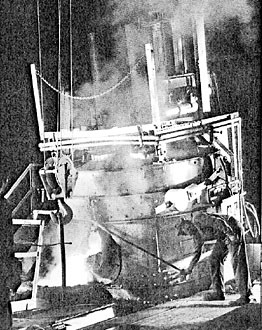

A Fort Pitt employee pours molten steel into a casting mold (photo from 1968 company brochure) |

|

Foundry casting was one of the earliest methods of shaping molten iron and steel into useful objects. To create a casting, first a pattern-maker carves wood or some other material into the shape that the metal will eventually take. The shape is pressed into wet sand to create a mold; if necessary, molds are taken of both the top and the bottom of the pattern, and inlets are added so that molten metal can be poured into the side of the mold.

The sand is allowed to dry and harden. If the shape has to be hollow in the center, a core of sand or some other material is created as well and hung in the center of the mold using wax or wire. Then the halves of the mold are clamped together; molten iron or steel is poured in and allowed to cool; the mold is removed; and the casting is cleaned and finished.

It sounds crude, but in the hands of talented pattern-makers and skilled foundrymen, fairly elaborate castings could be created:

Pattern-makers had to use a fairly complicated set of formulas to calculate the amount of "shrinkage" in the metal as it cooled, and adjust their templates accordingly;

Foundrymen had to use the correct consistency of sand to ensure accurate molds with many different types of steel and iron;

Men operating the melting furnaces had to use the correct mix of scrap, raw iron ore and other minerals to ensure that the metal produced had the appropriate hardness and strength for the type of casting being made;

Machinists and cleaners had to drill, grind, sand, and polish the finished castings to the customer's specifications.

Though the historical record doesn’t say for certain, when Fort Pitt opened in 1906 it was likely melting iron and steel in furnaces fueled by coke or gas. Within the next decade, it adopted new electric-fired furnaces whose temperature could be controlled much more carefully, and in 1921 the company and four competitors organized the Electric Steel Founders' Research Group to advance the technology even further.

Fort Pitt was particularly interested in improving sand mixtures to make more accurate, thinner, and lighter castings. With only 300 to 400 employees and a relatively small plant, Fort Pitt wasn't the largest foundry in the Pittsburgh area, but its size worked to its advantage; it helped bond Koch, his top managers, and his employees into a tight family that was able to innovate and collaborate, creating high quality castings at low cost.

Western Pennsylvania manufacturers like Westinghouse Electric, Westinghouse Air Brake, Babcock & Wilcox and others provided a ready market for Fort Pitt's products. Foundries produce relatively few castings for purchase by the general public. Instead, Fort Pitt made items for industrial customers, like pipe fittings and couplers for boilers and water systems; axle and bearing parts for railroad cars and locomotives; gears, hooks and chains for mines and factories; and pieces for large electric motors and circuit breakers.

Cooperation Breeds Innovation

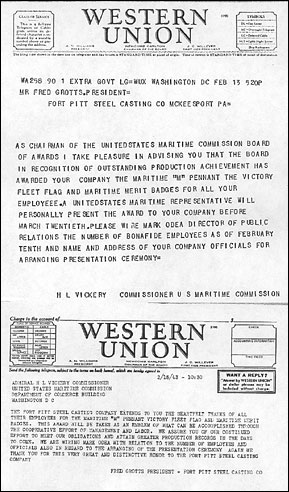

Koch's death in 1937 put the company into the hands of the Union Trust Bank as executors of his estate, but Fort Pitt Steel Casting continued to prosper under the leadership of his top lieutenant, Fred Grotts, who became president and saw the firm out of the Depression and into World War II, when employment topped 1,300 workers. Contemporary press accounts praised Grotts' "humane" and progressive management.

|

|

Telegrams to and from the Fort Pitt Steel Casting Co. after the foundry won a naval “M” award for excellence in wartime production (from 1943 company brochure) |

|

"He mingles and associates with his men, understands their problems, and is always ready and willing to mediate and conciliate little differences at the counsel table in the good old American method of give and take," said state Rep. Samuel Weiss, a Democrat from Glassport, in 1943, when Fort Pitt was awarded a maritime "M" award for efficiency and excellence in producing parts for naval warships. “If more employers practiced the simple philosophy of Fred Grotts, victory in this war would be quick and certain.”

Cordial relations didn’t prevent Fort Pitt’s employees from joining the new United Steelworkers union in the late 1930s, or protect the company from a brief wildcat strike by 43 welders in 1943. But the strike was condemned by both the union and management, and the welders went back to work after only two days.

In 1944, Pittsburgh’s H.K. Porter Co. purchased Fort Pitt (possibly to relieve the bank from the burden of management under wartime condition), then sold it at war’s end to Pittsburgh Steel Foundry and Machine Co. of Glassport. Though larger than Fort Pitt, Pittsburgh Steel Foundry’s line of products, which included locomotive parts and electric motor frames, complemented the smaller firm’s offerings. A new subsidiary, Pittsburgh Engineering & Machine Co., designed and built equipment for steel mills, which were struggling to keep up with postwar consumer demand for automobiles and appliances.

Then the destiny of Fort Pitt Steel Casting Co. changed forever in 1959, when Pittsburgh Steel Foundry was acquired by Textron Inc., a new industrial conglomerate that had grown out of a tiny Boston, Mass., textile company called Special Yarns.

With New England’s textile industry in decline in the 1950s, Textron went on what one its president, Royal Little, called a “buying spree,” acquiring automotive, appliance, aerospace and other companies that manufactured everything from ballpoint pens and staplers to chainsaws, plywood, pharmaceuticals, helicopters and golf carts. The Wall Street Journal called Textron “the conglomerate king,” and the company’s stock price soared, with shares split in both 1966 and 1967.

Conglomeration’s Toll

Conditions at Fort Pitt, however, began to deteriorate as Textron managers came and went; decisions once made in McKeesport or neighboring Glassport were now coming from Providence, R.I., and were made by executives who were only vaguely familiar with the steel industry. The once-close relationship between executives and the rank-and-file disappeared and Fort Pitt was struck several times in the 1960s. The plant’s technical edge on its competitors vanished, and then Fort Pitt slipped behind the industry when furnaces and casting equipment weren’t updated.

|

|

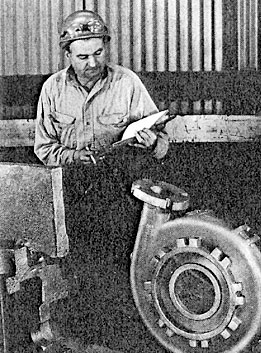

Going over blueprints and patterns for items to be cast in the foundry (photo from 1968 company brochure) |

|

In April 1968, Textron divested Fort Pitt Steel Casting to another conglomerate, Kearney-National Inc., which sold the company 18 months later to Condec Corp., a manufacturer of valves and pipe fittings based in Connecticut that was rapidly consolidating small foundries and valve makers across the mid-Atlantic states. Fort Pitt and its 500 employees, who averaged more than 20 years’ experience in a highly skilled field, seemed to be an ideal fit for Condec’s valve division. (Condec’s valve division, called “Conval-Penn,” is not related to Somers, Conn., based Conval Inc., which is still in business; Conval Inc. would eventually take legal action against Condec for violating its trademarks.)

Condec announced plans in 1972 to invest $1.7 million to update pollution control equipment and add a new, partially-automated facility for preparing sand for molds. When another Condec plant, the former Ohio Injector Co. near Akron, was closed, its finishing equipment was shipped to McKeesport.

A new contract with USW Local 1406 simplified work rules and added flexibility that promised to save Fort Pitt money; the total investment between 1973 and 1974 actually totalled $2.5 million. Managers called the improvements the most significant since the plant’s electric furnaces had been upgraded in the 1930s and said the investment would “ensure the future” of Fort Pitt Steel Casting.

But the problems of absentee ownership continued. In the 1970s, Fort Pitt had five different general managers, four different plant engineers, three different sales managers and two different personnel directors. Managers came and went and procedures and policies changed frequently, creating resentment and mistrust among employees.

Falling Behind

|

|

A Fort Pitt employee inspects a casting before shipping (photo from 1968 company brochure) |

|

Years of deferred maintenance had taken their toll as well. Despite the upgrades performed in the early 1970s, consulting engineers hired by Condec in 1977 concluded that the plant was in poor condition, with unsafe cranes and a roof that was falling apart. Inefficient work areas and outdated equipment reduced productivity, and overseas competitors who didn’t have to pay union wages were supplying both raw and finished castings that equalled Fort Pitt’s quality at lower cost. The consultants, Lester B. Knight and Associates of Chicago, concluded that Fort Pitt Steel Casting was losing almost $800,000 per year.

An immediate cost-reduction and efficiency program was recommended that would save Condec more than $1 million annually and enable Fort Pitt to show an annual profit of $338,000; also proposed was a three-year, $8.3 million renovation program to replace outmoded methods and add newer technology that customers wanted.

Knight’s consultants further recommended Condec expand the facility by 100,000 square feet at a cost of $20 million to produce “large, high-integrity type valves” that customers wanted.

When the contract with the Steelworkers expired at the beginning of 1978, Condec demanded that employees take wage and benefit concessions, and tension between employees and management finally reached the breaking point. Local 1406 voted to walk off the job in March.

Bargaining sessions through the spring and summer proved futile and threats flew back and forth as what General Manager James Spresser called “brinksmanship by both parties” resulted in “a position that neither side could back away from.” In November, Condec announced that Fort Pitt was closed permanently, putting 325 people on the unemployment line.

“Labor and management had an unfortunate relationship,” Spresser said, “and everybody’s sorry.”

Last Chance

|

|

Fort Pitt Steel was in serious decline before an employee-ownership group tried to save it. |

|

Then a savior appeared on the horizon in the form of Bill Cochenour, a McKeesport native working for the San Francisco investment bank Kelso & Company. Changes to corporate tax law made it possible for employees to purchase control of the companies they worked for by putting profits into a trust fund; after debts were retired, the money put into trust would be converted into shares of stock that would be held by employees based on their years of service.

Kelso was one of the pioneers of these so-called “Employee Stock Ownership Plans,” or ESOPs, and had already helped several manufacturing concerns out of bankruptcy and back into operation. Cochenour, learning of the troubles at Fort Pitt Steel in his hometown, put Kelso in contact with a labor-management group trying to save the plant.

Led by Spresser and other managers, employees agreed to assume $8.5 million in Condec Corp.’s debt in exchange for ownership of the plant. Allegheny County and the City of McKeesport agreed to invest $300,000; the federal government guaranteed 90 percent of a $2 million line of credit. The new, employee-owned corporation, McKeesport Steel Castings Co., began operation on May 1, 1980. Industry analysts and observers called it a model for other ESOPs.

|

|

A rough sketch of the plant’s layout, much as it remains today (click to enlarge) |

|

In retrospect, trying to salvage Fort Pitt Steel Casting was probably impossible for any start-up company, even one founded with such good intentions. The antiquated plant was no longer competitive, and despite a multi-million contract to supply valves and pumping parts for oil companies, and a much reduced workforce of only 100 people, it continued to lose money. On Sept. 26, 1983, McKeesport Steel Castings declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

An unnamed spokesman told the McKeesport Daily News that the company had every intention of staying in business. The bankruptcy, he said, “allows the company temporary relief from its obligations while searching for sources of new capital.”

Yet with the U.S. steel industry wracked by foreign competition and recessionary conditions, looking for new capital was futile. By early 1984, operations at McKeesport Steel Castings had all but ceased. Cleveland investor Herman Brownstein purchased the plant in June 1984 and renamed it McKeesport Steel Foundry Inc., but it’s unlikely that many castings were shipped, except those necessary to fill existing contracts. When utility companies sued because their bills were going unpaid, the plant closed for good and was abandoned.

(Condec faired little better in these years. A “poorly managed company and a poor stock,” in the words of one Wall Street analyst, it was taken private, then broken up when the principal investors defaulted on their debt.)

In 1995, the city used part of the Fort Pitt Steel Castings property to incinerate debris from houses that were being torn down, and three years later the plant was designated a “Keystone Opportunity Zone,” which offers potential developers 12 years of state and local tax abatements if they choose to build there.

Few developers, however, want the expense of tearing down a dilapidated plant and coping with environmental problems caused by years of metal and solvent contamination. Despite its location along the Youghiogheny River, a state highway (Route 148) and the new Cumberland-to-Pittsburgh biking and hiking trail, the Fort Pitt property remains abandoned to the elements more than 20 years after the last employees clocked out.

Sources

About Textron: Company History, Textron Inc., retrieved from www.textron.com on July 15, 2007.

Brown, Warren, “Jobless Steelworkers Want to Go Into Business,” The Washington Post, Dec. 12, 1979, p. A1

Cooper, Donald R., “$1.7 Million Modernization Set by Fort Pitt Casting,” The Daily News, McKeesport, Pa., April 21, 1972, p. 31.

DaParma, Ron, “Employee-Owned Factory Stumbles,” The Daily News, McKeesport, Pa., Sept. 27, 1983, pp. 1-2.

“Firm charged of bargaining in ‘bad faith,’” United Press International, Dec. 15, 1978.

Fort Pitt Steel Casting Co. press releases, Fort Pitt Steel Casting Co. file, McKeesport Heritage Center, McKeesport, Pa.

Fuoco, Linda Wilson, “Trial by fire,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 15, 1995, p. S-1.

Glassport, Pennsylvania: It Happened Here (Glassport, Pa., Bicentennial Committee, 1968).

LaRue, Gloria T., “Court rules utility can be paid with sales of secured collateral,” American Metal Market, Oct. 22, 1986.

Marcus, Steven J., “Dissidents and deficits beset Condec,” The New York Times, Nov. 8, 1983, p. D-4.

Samudovsky, Kathy, “3 sites proposed for new business,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Dec. 27, 1998, p. EW-1.

Services and Facilities of Fort Pitt Steel Foundry, Kearney-National Inc., 1968.

“Settle Two More Steel Strikes,” United Press International, Nov. 9, 1965.

Siver, Frank, Email to author about Conval Corp., Jan. 13, 2013.

Spresser, James, Letter to Kelso & Co., May 7, 1979.

Spresser, James, The McKeesport Steel Story. Unpublished manuscript at McKeesport Heritage Center, dated Oct. 2, 1979.

“3 Pittsburgh Area Plants Struck By Steelworkers,” The New York Times, Sept. 30, 1963, p. 41.

“Strikers Agree to Resume Work in McKeesport,” United Press, Jan. 12, 1944.

“The Philosophy of Fred Grotts,” The Associated Press, March 29, 1943.

“Workers organize, form company,” The Associated Press, Oct. 25, 1979.

---

© 2007 Jason Togyer, all rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part without express permission is prohibited. To get permission to republish this article, please send email first initial and last name at gmail dot com, or write to Tube City Online, P.O. Box 94, McKeesport, PA 15134.

Comments, corrections and additions are welcome! Write to first initial and last name at gmail dot com. This article is from tubecityonline.com/steel, the Steel Heritage section of Tube City Online, P.O. Box 94, McKeesport, PA 15134.